‘Every hour of sleep before midnight is worth two after midnight.’

G’day groovers! I’m going to make a case for that old adage “Every hour of sleep before midnight is worth two after midnight”. You and I both know the quality of our sleep is extremely important and experience has taught us that going to bed late just isn’t a sustainable habit.

For most of us, the more late nights we have, the more fatigue and drowsiness we’re likely to experience over the ensuing days. That being said, is there a case to be made for the first few hours of sleep (in this case those before say 1am) being proportionately more restorative than the hours at the tail end of our sleep cycle? I believe so.

Fig 01. This coalition of cheetahs partied hard ‘till 3am and as a result are completely oblivious to that herd of delicious wildebeest passing merely metres away!

It seems however that not everybody agrees. Some experts in the field of sleep science claim the adage is an overstatement and that sleep quality should not vary wildly as long as the duration and time of the day/night are consistent. Even so, a rudimentary understanding of sleep phases and a gentle meander through the wealth of scientific literature on the effects of positioning one’s major sleep block earlier or later in the night present a pretty convincing argument that the adage holds true. In order to get that basic understanding of how sleep works, let’s have a brief look at the major sleep phases.

The Two Phases of Sleep

Deep (non-REM) sleep is the more restorative phase associated with mind-body recuperation, synthesis of complex proteins for tissue repair and maintenance, muscle growth, brain glial cell restoration, learning and memory formation and the maintenance of brain/nerve synapses. Interestingly, deep sleep is believed to occur in a slightly ‘lop-sided’ or asymmetrical fashion in that the brains left hemisphere has been observed to sustain a greater level of neural activity than its right hemisphere, apparently supporting a degree of ‘vigilance’ to our external environment and therein allowing for rapid awakening in the event of a threat.1

Deficiency of deep sleep is linked to hypertension[2] (high blood pressure) and also correlated with a high degree of specificity to depression, apprehension and steep reductions in performance.[3]

Rapid eye movement (REM), the other major sleep phase, dominates after birth and gradually diminishes over our life span. REM is the sleep phase where vivid dreaming is most likely to occur and contributes somewhat to the integration of procedural, spatial and emotional memory and to several lesser physiological roles yet to be properly defined.

REM deprivation is understood to lead to death after more than 6 months in some mammals although this has not been observed in humans. While the major negative effects of REM deprivation are yet to be clarified, conversely it has been demonstrated to temporarily suppress some symptoms of depression.[4]

Considering also that therapeutic doses of anti-depressants including SSRI’s have been shown to stop REM sleep for up to a few months without major deprivation effects, it’s hard to make the case that consistent REM sleep is critical to human health in general in the medium term.[5] So on the face of it, it would appear that REM sleep, although possibly crucial to long-term health, is not as acutely important as deep sleep.

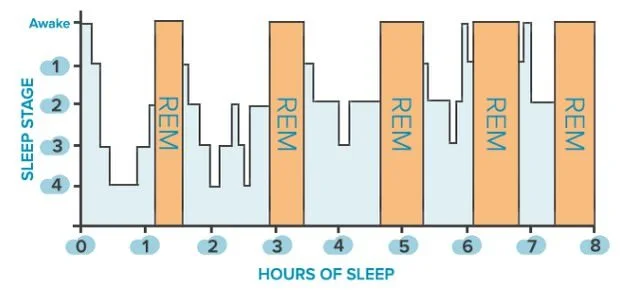

Fig 02. Relative frequency and duration of the two dominant phases of sleep. Deep sleep phase in light blue. Image – Google ‘labelled for reuse’.

The Science of Sleep Quality

Starting our sleep block from later in the night, say from 1am to 9am appears to reduce the quality of our sleep. In their 2019 study, Facer-Childs et al observed that a sleep phase advance (shifting forward sleep time) of two hours carried out by ‘night owls’ was accompanied by “significant improvements to self-reported depression and stress, as well as improved cognitive (reaction time) and physical (grip strength) performance measures” later in the day when delayed sleep usually would have led to drowsiness and fatigue.[6]

Likewise and for decades research has established that levels of depression, anxiety and a sense of well-being are adversely effected by the irregular sleeping patterns of night workers such as bar tenders and paramedics.[7]

Fig 03. Are ‘night owls’ paying a price for delayed sleep?

Here’s the crucial bit. Long duration sleep tends to run in fairly stable 90 minute cycles, each encompassing phases of both deep sleep and REM sleep. With deep sleep being more prevalent in the first half of the night and REM sleep more prevalent in the second half of the night. So if sleep phases perform distinct functions and benefits AND they occur disproportionately at different times of the night then shouldn’t the time of night over which we sleep make a difference in the benefits of rest we receive?

I certainly believe so. By sleeping earlier we are likelier to spend a greater portion of our overall sleep in the deep sleep state at least in part because of the aforementioned propensity for longer deep sleep phases earlier in the night.

Proverb vs Science

Adages and sayings such as the title of this article are a reflection of the collective experience of populations over millennia (or centuries at least). In the realm of something as fundamental to health as sleep there is also a clear absence of any counter traditions or axioms promoting skipping or delaying sleep. Survival pressure promotes abiding by traditions that produce better survival outcomes. Better survival outcomes probably come about due at least in part to higher quality of sleep.

From my own personal experience I can say confidently that as long as I’ve slept fairly soundly for the first few hours (say 9.30 to an hour or so after midnight) then regardless of how disturbed the later sleeping hours may be, I’ll not suffer from any effects of sleep absence.

Conclusion

I’m convinced that for the most part ‘night owls’ think going to bed late brings them no ill effect when in actual fact it most likely does. The continuation of blue light exposure into the evening from smartphones, computers, TV’s and light fittings drives cortisol (a stimulation hormone) production beyond it’s natural reduction hour and in consequence delays the onset of melatonin (the ‘sleep’ hormone) production. Not to mention the relative ill health of night shift workers.

Discussing these issues at length is however for another day.

While precisely quantifying the restorative difference between hours slept before and after midnight is clearly impractical if not a ‘fools errand’, I’m satisfied the preponderance of evidence suggests sleeping earlier rather than later is the wiser choice.

Here are some simple steps you can take in order to improve your restorative sleep:

Try to make your bedtime when the sun goes down or at most a couple of hours after.

Focus on winding down an hour or two before your planned bed time.

Apply blue light-restricting measures wherever possible.

Prioritise reading over viewing screens. Allowing your cortisol production to drop off and your melatonin levels to naturally build.

Drink less alcohol. It disturbs sleep. Period.

There it is. Sleep early. Sleep tight. Nite.

References:

1 Tamaki, Masako, Ji Won Bang, Takeo Watanabe, and Yuka Sasaki. “Night watch in one brain hemisphere during sleep associated with the first-night effect in humans.” Current biology 26, no. 9 (2016): 1190-1194.

2 Javaheri, Sogol, and Susan Redline. “Sleep, slow-wave sleep, and blood pressure.” Current hypertension reports 14, no. 5 (2012): 442-448.

3 Dijk, Derk-Jan. “Slow-wave sleep deficiency and enhancement: implications for insomnia and its management.” The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 11, no. sup1 (2010): 22-28.

4 Ringel, Brenda L., and Martin P. Szuba. “Potential mechanisms of the sleep therapies for depression.” Depression and Anxiety 14, no. 1 (2001): 29-36.

5 Markov, Dimitri, Marina Goldman, and Karl Doghramji. “Normal sleep and circadian rhythms: Neurobiological mechanisms underlying sleep and wakefulness.” Sleep Medicine Clinics 7, no. 3 (2012): 417-426.

6 Facer-Childs, Elise R., Benita Middleton, Debra J. Skene, and Andrew P. Bagshaw. “Resetting the late timing of ‘night owls’ has a positive impact on mental health and performance.” Sleep medicine 60 (2019): 236-247.

7 Khan, Wahaj Anwar A., Russell Conduit, Gerard A. Kennedy, and Melinda L. Jackson. “The relationship between shift-work, sleep, and mental health among paramedics in Australia.” Sleep Health (2020).

All images Google Images ‘labelled for reuse’ and Unsplash.

To work with Andy, please schedule a consult at https://www.healthcoachandy.com

P.S. If you'd like to explore my proven approach to fixing your metabolism so you can lose fat forever and always fit your fave clothes, book a call. Let's see if I can help you with that. Crash diets only work in the short term. Metabolic fat loss solves your "shrinking wardrobe" problem by fixing the root cause: a body that has forgotten how to burn fat.

Recent HCA Instagram posts: